On Returning

Part I: Bumalik

In San Pascual, a remote village in the northern Philippines, I fall in love for the first time. Sitting by a campfire with new friends Adam and Anna, drinking cheap beer under a glittering night sky, it is not the love of a person, rather, with a place, a feeling, a scene, a moment in time. It is the love of being somewhere else, of being out in the world, of newness and vitality. The love of travel, and it feels as though it will last a lifetime.

This place, San Pascual, nestled high in the mountains, is our temporary home, our group of twelve who are taking part in a volunteering program. For those whose home it is permanently, they have welcomed us with open arms and hearts, as they have in the neighbouring villages of Apni and Lumes. We share and learn through food, dance, and storytelling, and fall deeply in love with it all. The village life, of roosters crowing in the morning, of rising with the sun, of eating river fish and freshly slaughtered chicken, of walking everywhere, of singing karaoke and drinking poor quality gin, and of sleeping under the stars. It is intoxicating, invigorating, it is love.

Nearby the softly crackling campfire, a set of rickety wooden tables and plastic chairs comprise our kitchen and dining area. It is where we gather each morning and night. We cook improvised meals, share stories of our days, discuss twenty-something politics and philosophy, celebrate a birthday, and nurse those with stomach aches. It is where the Elders meet with us, and where curious and playful children know where to find us. It is our place in San Pascual. We live in in the village for two months, and in the words of Thoreau, live deliberately, sucking out all the marrow of life while we are there. As such, a part of each of us is sewn into that earth.

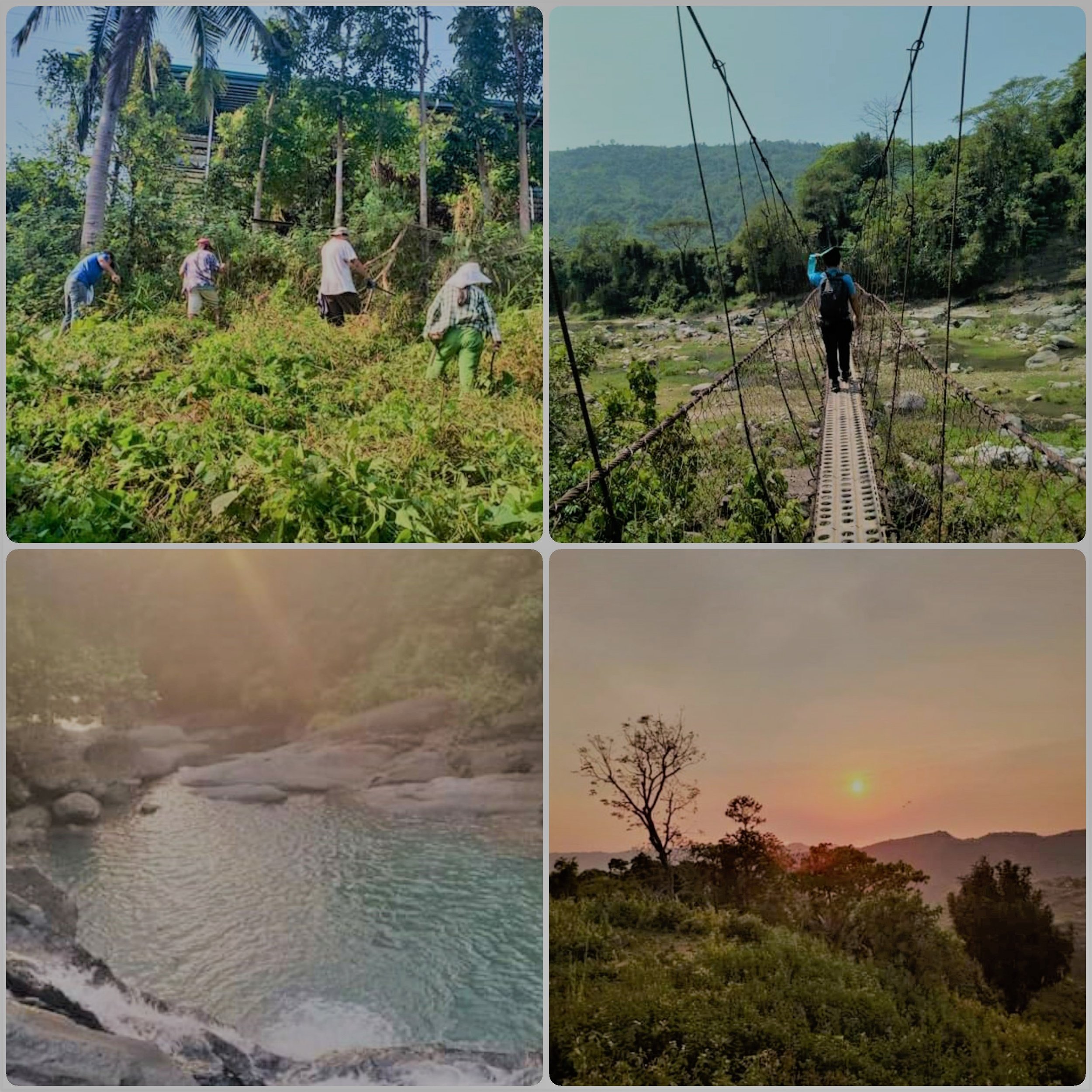

Images from San Pascual, Philippines

Two years after leaving San Pascual, amongst a flood of collective tears and heartfelt promises to write, I return. In Baguio City I meet Digna, a social worker who acted as the conduit between our group and the communities. She will accompany me and help with interpreting and accommodation. There is only one jeepney per day to San Pascual, and we hurry to the depot to secure our seats. The route passes Asin Hot Springs, across a newly constructed concrete bridge near Nangalisan, and then begins a slow crawl up a sometimes paved, and otherwise rocky and bumpy mountain road. Along the way I look out for familiar faces, and find my memory triggered by houses, trees, sounds, and bends in the road.

The village is deserted when we arrive, with families working at their rice fields, and children at school. We hear the distant echoes of voices, and the songs of birds, in the otherwise silent mountains. On the ground where we gathered, where we shared meals, laughter, and tears, where our memories were sown and young hearts nourished, a lone goat is munching on the grass. A wooden stake has been driven into the ground and holds the goat in place. The goat chews loudly, paying me no attention, and rips another tuft from the earth. With each mouthful, a disquiet curdles inside my stomach. I want to wrench the stake from the ground and shoo the goat away. This ground is ours, it is sacred, special, a place of happiness and love, not a grubby old patch for goats to rummage. Of course, it is none of this. It is not sacred, nor special, except for the place it holds in my memory.

‘Our place’ in San Pascual, 2006

Returning to San Pascual is my first confrontation with the bittersweet sensations of return, a heady mix of sorrow, warmth, fear, and heartache. The ocean of my memory is restless, a tormented sea, and its hostile currents drag sunken relics from the depths. They bob on the water’s surface as I tread water. In a nearby Ficus tree, appear mirages of children taunting a green tree snake. They throw stones and bottle caps and scream excitedly. Amongst the haunting silence of the early afternoon, ghosts appear everywhere. Our group sharing a meal, Nat sat there, Peter here, Therese over there. Their laughter and conversations are swept away in the breeze. Now, the ground is overgrown and littered with goat droppings. I sit on a concrete step and remember. Over three nights, I visit old friends, hearing who is married, who has moved away, and who has passed. After returning to Baguio City, I am unsure if it was wise to return.

Part II: Kurudi

In Engosengiu, a rural village near Arusha in Tanzania, I fall in love again. Tanzania becomes home for two years, rather than two months, and work includes managing a women’s education program. Throughout the years love develops for people, scars me in moments, and seduces me once again, with the unhurried and elementary nature of village life.

Amina is someone easy to love. She lives in the slum area outside Arusha known as Unga Ltd, named after a flour factory that once operated there, its weathered silos still standing, years after the factory closed. Amina lives in a boxed concrete home with her daughter, Hadijah, and her auntie, uncle, and cousins. The simple abode is adorned with framed family photos, Islamic paraphernalia, and a plastic clock with a stuttering second hand. Originally from the coastal town of Tanga, Amina’s parents died when she was a child, and Hadijah’s father fled from his responsibilities, and has never met his daughter.

Unga Ltd, Tanzania

Amina is slight in stature, though what she lacks in size she makes up for in personality. Having to fend her herself from an early age, Amina is outspoken and forthright. In the claustrophobic, winding, maze of alleyways of Unga Ltd, Amina holds her ground, and scolds drunk or rude men who present as an obstruction or nuisance. A few select words and her glare are enough to see a grown man wilt before your eyes. At the markets in town, Amina bargains hard for clothing and school supplies and has no qualms walking away if the vendor is being unfair. ‘Let’s go,’ she huffs, ‘to another one. I don’t like this man!’ Underneath Amina’s tough exterior is stowed a wicked sense of humour and a knack for practical jokes. She is observant, and mocks people’s mannerisms and accents. Amina is happy to play the fool, to bring a smile to others.

Amina’s home is a short way from the main street that runs through Unga Ltd, a sickly grey, earthen path, potholed and neglected, shared with pedestrians, Maasai women herding cows, and the ricketiest dala-dalas (minivan taxis). Whenever I pass by, squashed inside a dala-dala, I peer through the contorted bodies and see if Amina is there. Sometimes she is, washing clothes or chatting to friends in the salon, sometimes not.

I leave Tanzania, after two years, amongst a familiar flood of collective tears and heartfelt promises to stay in touch.

On my third return visit in as many years, I arrive at Amina’s home with Jamila and Asha, two of her best friends. The house is overflowing, with relatives, friends, and neighbours. They spill out onto the pathways around the entrance, sitting on plastic chairs and prayer mats, underneath weathered blue tarps that enclose the shanty dwellings. The volume of conversation is gentle, a solemn, reverberating hum. Asha picks up Hadijah, holds her tightly, and Amina’s auntie greets us and thanks us for coming. We negotiate a path through the crowd, towards the entrance of the house. We pause at the doorway, and a crushing wave of sorrow engulfs me. I remember the last time I saw Amina, twelve months earlier, ‘See you next time,’ she beamed, as the taxi pulled away. Perhaps sensing my hesitancy, Asha passes Hadijah to me. She is still too young to understand what has happened, and I am not sure she remembers me. She stares with curious eyes, and we all stand in silence. Jamila is the first to speak, ‘Stu, Amina is gone,’ her voice is laced with confusion and indignation. Unable to speak, I nod instead, acknowledging the tragic reality.

Gathering in Unga Ltd

Two months earlier, a loud and violent disturbance in Unga Ltd drew many residents from their homes. A scuffle between a group of men resulted in debris, of which there is ample supply in Unga Ltd, being thrown between the warring parties. Amina, as curious as ever, was amongst the onlookers. Struck in the stomach by a piece of flying debris, Amina was rushed to hospital however did not survive. Hadijah, like her mother, was orphaned in her childhood.

Part III: On Returning

Our memories of travel often distort with the passage of time. We romanticise our privations, from the comfort and safety of our armchairs, and downplay our hardships, as our anecdotes are embellished with each recital. The pains of our travels inevitably fall, those cliffs of despair crumbling into the ocean, swallowed by the memories of joyful adventures, eroded by the kindness of strangers, and the thrill of setting foot in foreign lands. In the wake of the storm, we bathe in our happiest memories, reminiscing over the friendships, romances, songs, and laughter.

Returning to places we have travelled, lived, loved, we are inevitably thrust back to our former selves. If we are ill prepared, it can be a violent, hurtful realisation. Confronted with someone we no longer recognise, have moved on from, or have grown to disown. The exhumation of memories, the resurfacing of feelings, the recollection of declarations and mistakes, it can be a painful experience. We chased a dead love to the red centre, and never returned.

Or perhaps we have been forgotten or enshrined. Where once we were recognised, and felt a sense of home, we are now a stranger, or only a memory in the minds of others. We are that image in the photo, frozen in time and recounted in tales, a two dimensional character in the fables of others.

Leaving San Pascual for the second time, I reflect that it was wise to return. The torment of the goat ripping at our hallowed turf eventually dissipates. Everything changes, life is not static. Those memories of twenty something conversations around the campfire, of drunk karaoke, and of homestays with freshly slaughtered chicken, they settle in a comfortable place. Bobbing along on the surface, and I can smile as they float by. There is no need to fish them from the ocean, breathe new life into them. Instead, let them drift, leave them be, and greet them when they pass.

When leaving Engosengiu, the dala-dala splutters along the road to Unga Ltd. With each incoming passenger the sliding doors grate on their contorted tracks, grinding and piercing. Soon enough, we pass by the way to Amina’s home. The realisation that I will never see her there again, holding Hadijah’s hand, joking with her friends, washing her clothes, it drags me under, and I struggle for air. The crowd of bodies inside the dala-dala provide ample protection for my tears, and with a violent thrust of acceleration we turn a corner, and the moment is over. While it was painful, returning was necessary – and it will continue. Those embers that ignited years ago, they caught alight. Fuelled by adventures, hardships, friendships, and love, they burned stronger. The inferno has since engulfed me, and it will last a lifetime.